Little is definitively known about the early life of Pontius Pilate, but most scholars believe he was born into an equestrian family, a class just below the Roman Senate.

His rise to power suggests a strong political network and Roman military experience. His status placed him among those eligible for governance in distant imperial provinces.

Around 26 CE, Pontius Pilate was appointed the fifth prefect of the Roman province of Judea under Emperor Tiberius. This region was known for its tension and religious unrest.

Unlike senatorial provinces, Judea was under direct imperial control, making the role of prefect more militarized and focused on order and taxation rather than civic development.

Pilate’s tenure began with decisions that alienated the Jewish population. He introduced Roman military standards bearing the emperor’s image into Jerusalem, sparking protests.

Though initially refusing to remove them, Pilate eventually gave in, showing he was willing to compromise. However, his relationship with the local population remained strained.

Pilate later used Temple funds to build an aqueduct, again angering Jewish leaders. When protests erupted, his soldiers disguised themselves and violently suppressed the dissent.

His approach to leadership was often seen as arrogant and culturally insensitive, failing to recognize the deep religious convictions of the people he governed.

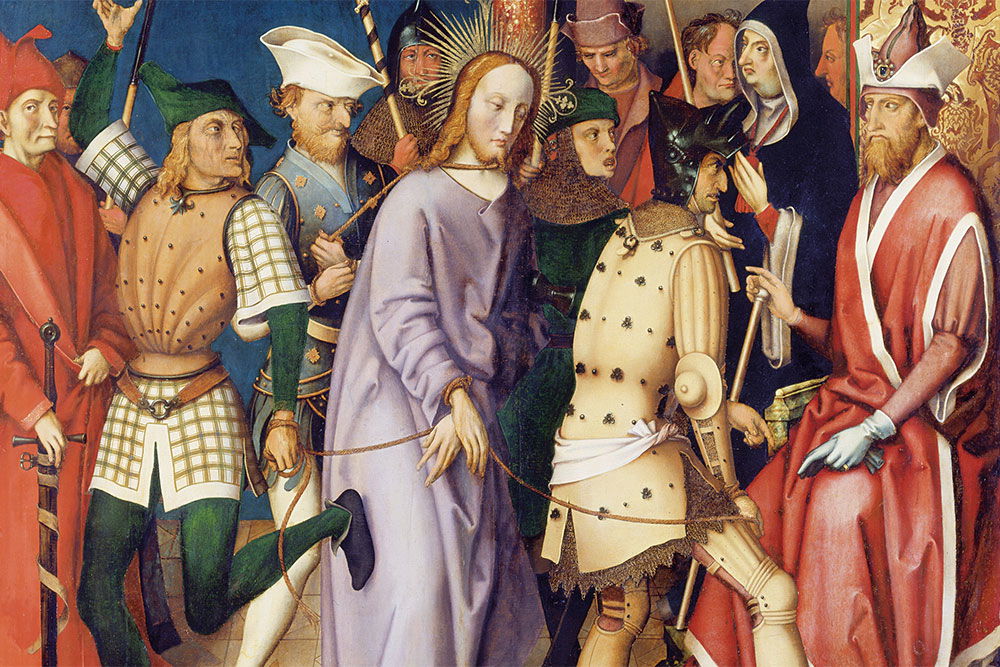

The most famous moment of Pilate’s career came during the Passover festival when Jesus of Nazareth was brought before him by Jewish religious authorities.

They accused Jesus of claiming kingship and challenging Roman authority. Pilate initially found no guilt in Jesus but faced mounting pressure from the crowd.

Pilate’s decision was politically delicate. Executing Jesus might avoid unrest, but it could also be unjust. He attempted to release Jesus by offering the crowd a choice.

When they chose Barabbas instead, Pilate washed his hands publicly, declaring himself innocent of Jesus’ blood. This act became symbolic in Christian tradition for moral evasion.

Though reluctant, Pilate ordered Jesus' crucifixion, a method of execution reserved for non-Romans and rebels. He had the title “King of the Jews” placed above the cross.

This inscription angered the Jewish authorities but Pilate refused to change it. His message conveyed the Roman perspective on sedition and authority.

Historians and theologians have debated Pilate’s role in Jesus’ death for centuries. Was he a weak administrator, a calculated politician or a man caught in a moral crisis?

Some sources portray him as cruel, while others suggest he tried to free Jesus but bowed to political pressure. The Gospels give varied but overlapping narratives.

Non-Christian sources like Josephus and Philo mention Pilate. They describe him as inflexible and harsh, particularly critical of his insensitivity to Jewish customs.

Archaeological evidence also confirms his role. In 1961, a stone inscription bearing his name was found in Caesarea Maritima, confirming his historical existence.

Pilate’s rule ended around 36 CE after he violently suppressed a Samaritan uprising on Mount Gerizim. The backlash was strong enough to warrant his removal.

He was summoned to Rome by Lucius Vitellius, the governor of Syria, to explain his actions. What happened afterward remains unclear, but he disappears from historical record.

In Christianity, Pilate’s role is both tragic and essential. He is remembered as the man who sentenced Jesus to death, yet also as one who declared Jesus innocent.

Some traditions view him with sympathy. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church even regards him and his wife as saints, though this is rare among Christian denominations.

Pontius Pilate has been portrayed in countless works of art, film and literature. From Dante’s “Divine Comedy” to Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita,” he appears as a conflicted figure.

These portrayals explore themes of authority, conscience and responsibility, capturing the enduring fascination with his part in one of history’s most consequential trials.

Some view Pilate as a cruel enforcer of Roman rule, while others see him as a symbol of bureaucratic compromise, doing wrong to avoid worse outcomes.

He may have been a typical Roman official caught between empire and unrest, trying to maintain order in a politically volatile region with limited options.

Pilate’s name is forever linked to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Whether he was acting out of fear, pragmatism or duty, his decision had global consequences.

He has become a symbol of moral hesitation, a figure studied not only in theology but in political philosophy and historical ethics.

Pontius Pilate was more than a Roman bureaucrat. He was a man caught in the collision of empire, religion and history, whose choices shaped centuries of belief.

His story challenges us to consider how power is used, how justice is administered and how responsibility endures across generations.